Style vs Substance — an analysis of Laal Kabootar

- Abdullah Shahid

- Apr 27, 2020

- 9 min read

Cinema, inherently, is very intentional. The choices a director makes in their film dictates exactly how the story is played out on screen. If two directors were to make a movie out of the exact same script, the result would not have an iota of similarity between them. Each of the directors will bring a unique perspective that has been fueled by their experiences, their inspirations and their own ideals. Attempting to understand a director’s decision in their film unlocks a whole new film within the one you are watching and that is precisely what I love about cinema.

That being said, let’s talk about Laal Kabootar. It’s a rare Pakistani film where you can actually feel the intention behind the decisions and the way the camera moves. We only have one lens through which we can see the events of any film unfold — through the camera. What it sees is all we are allowed the privilege of seeing. The way the shot is framed, the way the camera traverses through time and space and what it chooses to show and not show is all information that we are supposed to learn and infer from. No shot is wasted and every frame means something. Thus, the question is, what is the effect of any given shot? What does it do?

The opening shot is perhaps the most important one. It introduces us to the world and sets the tone for the rest of the film. In Laal Kabootar, the opening tracking shot — as we move through a traffic jam caused by a car accident turned brawl, we understand something important: Karachi, as a city, is a major character in this film. A simple wide shot reflecting the fight and the surrounding cars would have been enough to convey the information needed for the story but this adds a layer of immersion that would have been lost on us otherwise. We feel like we are walking through the chaos shown on screen because the camera literally walks through it with us. Witnessing the ugly fight in the middle of a road as people look on is a shared experience that any Pakistani who has ever stepped out onto the road can relate to. The noise, the smoke, the people — all serve the purpose of grounding us closer to the very action that will pay off in the next few minutes as we witness the murder that will initiate the events of the film. It is truly no wonder this film was lauded for its vivid and accurate portrayal of Karachi.

Another recent incredible film that featured the city it was set in as THE main character was Joe Talbot’s 2019 film The Last Black Man in San Francisco. It took the idea of the city as a character and ramped it up in it’s opening montage to make one of the most beautiful and innovative opening sequences in contemporary cinematic history. The idea in both these films are the same, though executed differently. Kamal Khan uses it as more of an establishing shot where we are introduced to the character of the city whereas Joe Talbot uses it to basically outline the whole plot of the movie right there. We see the relationship between the two main characters, the city they live in, the similarity between the protagonist and the architecture of San Francisco and how all the different people react to two black men skateboarding down the street. A whole separate analytical piece could be written on the opening montage of that film and I urge you to watch it:

While the aforementioned tracking shot is not the main focus of this essay, all of this is to establish the depth that lies behind the direction of Laal Kabootar and the importance of what the camera is doing. Soon after the opening tracking shot, we meet one of the two protagonists of the film, Mansha Pasha’s Aaliyah Malik. She sits in her car with her soon to be slain husband enjoying some light-hearted banter, while being blissfully unaware of the horrors that lay ahead for her. We are given this shot/reverse shot combo:

The second shot is the point of view shot illustrating what Aaliyah sees through through her car window. It is partly obscured by the car in front of her and we see the brawl unfold in a kind of voyeuristic fashion, through a crack in the traffic. We understand the geography of the scene and know where whose eyes we are seeing this scene unfold through. This shot makes sense. It is both stylish and necessary. And it was this shot that inspired this whole essay.

As the film progresses along, there are multiple instances of the same type of shot being used in different contexts. However, it seems that we begin to lose the meaning behind this shot in favor of formalism. Here, I use the term formalism to describe an emphasis on the form of film itself rather than on the content of the film. And this is an important point to focus on when you’re actively viewing any film. The debate between formalism and realism rages on between film critics and theorists alike, if there is any interest in learning a bit more about it in an extremely accessible way, Patrick (H) Willems has a great video essay on it.

The opening shot and then this subsequent shot/reverse shot are responsible for helping us understand the language of this film. Each film provides it’s own language and good films are able to teach us this language and abide by it consistently to give us a journey we can enjoy and, just as importantly, easily understand. When a film breaks its own rules for no apparent reason, the audience is jarred even if they are unable to figure out why.

Later on, we see the same shot when Aaliyah meets the man whose brother she suspects was killed by the same man with the laal topi. If you watch the scene (starting around the 24 minute mark), it is filmed with two camera placements in mind. Firstly, the perspective of Irshad, whose office we step into. He sees Aaliyah and so all of those shots are set full within the office, no hidden agendas, because that is whose eyes we are seeing this unfold through:

However, the reverse shot, Aaliyah’s perspective of Irshad, is framed slightly differently. We stand just outside the office and see the frame of the door in the shot. The way you would stand if you were eavesdropping on someone’s conversation, if you weren’t actually invited into the office. Much like the way Aaliyah is treated in this scene:

Even to us, it feels like we are not allowed to be here. That we are doing something illegal or immoral by visiting this man. And that is exactly the feeling this scene is attempting to convey. We are outsiders to this world of crime and hired killers. We should not be here, even in the safety of our homes and/or our lavish theaters. Subconsciously, we register the effect of this shot. This rings true even more for someone from an upper class background like Aaliyah who is attempting to navigate this world without any experience or clue of how to find the killer of her husband. This, in my opinion, is truly intentional film-making. Where you say more with visuals than having to rely on exposition.

What distracts me from the immersion of this scene is how the scene continues after Aaliyah leaves the office. We continue to look at Irshad from the perspective that the film has established as her perspective. We even see the film move this handheld shot to look at him through the gaps of the papers pasted on his window:

This, I don’t understand. Here, it seems style was favored over substance. Whose perspective are we seeing through? Would it not be better to be in Irshad’s office and see him in perhaps a close up that would indicate his heightened state of frenzy? The handheld accomplishes that but the obscured shot does not. It is, undeniably, an innovative way to show this action play out but it does not help me resonate with Irshad’s fear and indecision in that very moment.

The more I thought about this shot, the more it began cropping up in Laal Kabootar. It seems Kamal Khan and cinematographer, Mo Azmi have a special affinity for this framing method. Popped up here as well, for the same location:

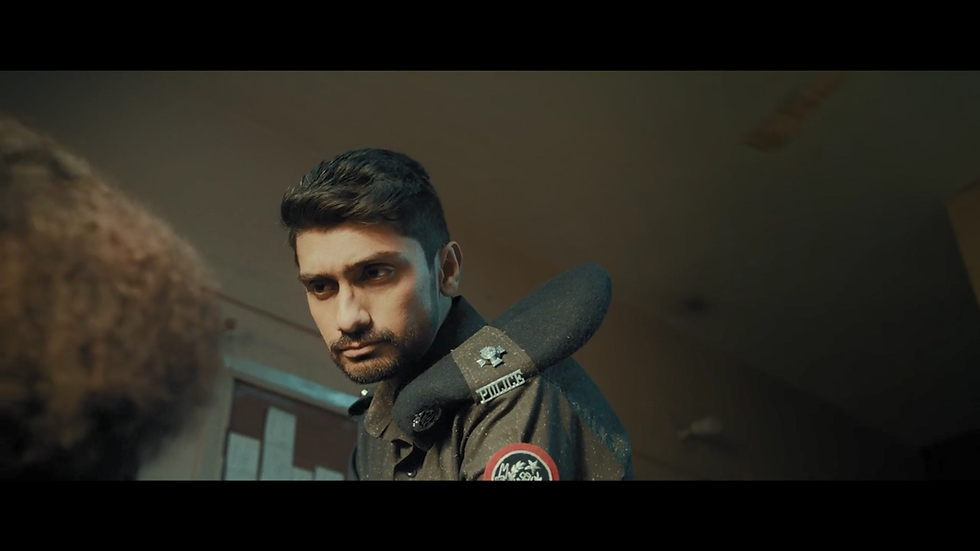

As a slight digress, I also wanted to talk about how much I enjoyed the way they used high and low angles to communicate who has the power in the above scene. It’s a simple technique but it’s effective and a joy to watch. The police is framed at a high angle — thus bigger and more powerful and the man being questioned is always at a low angle, making him look small and meek. Not to mention that the officer has lots of empty space behind him, he is in control and does not feel trapped. On the other hand, the man is surrounded by the chair, the background and the officer himself and the shot feels more claustrophobic and we get the feeling of being surrounded, which he undoubtedly is. This is a prime example of simple and excellent film-making.

High angle, empty background.

Low angle, cluttered background and foreground.

The crack in the wall shot makes another appearance when the police raid Adeel’s house and break up the scuffle happening inside (around 54 minutes in) which, by the way, is filmed through some magnificent long takes (a specialty of Kamal’s). We switch between two shots, both of which show the police pounding on the gate. One is through the crack of a barely open gate and the second is just a regular medium wide shot.

Through the crack.

Medium wide shot.

This one, I was even less able to comprehend the reasoning behind it other than it being a stylistic choice as the obscured shot does not make any sense in the context of the scene to me. There is no other perspective here to look through and even if there was, why do we only look through that perspective half the time and switch to the other medium wide shot the rest of the time? It implies that there is a third party present that is stalking these police officials. A shot like this wouldn’t even be out of place in a horror movie — a creepy stalker following his victims, it would instill the feeling of dread perfectly.

Famously, the master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock has used this shot in his most influential horror film, Psycho. However, here the intention is for the viewer to be literally in the shoes of a man partaking in his perverted tendencies to spy on women in their hotel rooms. We look through a hole in the wall he has created to see a somewhat similar shot:

Of course, this is a horror movie with completely different intentions but it is always interesting to see how similar shots are used in different contexts.

An argument can be made against my observations that not every shot shows the perspective of somebody or something — sometimes the camera serves to be a third person omniscient entity that just shows us what’s happening on the screen. And this very well may be true, but if it is, it is not in tune with what the film has previously shown us. And that is why I think it is important to adhere to the language your film has created. Along with style and substance, consistency is an important aspect of film.

However, the following chase is done so well that all these minor grievances were put to rest. It’s a difficult challenge to make an action chase scene that is edited well enough that we feel the craziness and the stakes of the situation but at the same time is completely coherent and Laal Kabootar manages to pull it off effortlessly. It felt extremely reminiscent of the on foot chases in Anurag Kashyap’s Gangs of Wasseypur and Ugly, both of which I am sure were big inspirations for this movie.

This whole essay may not seem as big a deal and may sound very ‘nitpicky’ but I believe that is the fun of cinema. Great auteurs in history have worked hard to make sure every frame and every tiny detail is relevant and meaningful. Everything we see represents something and I am thankful that a movie in Pakistan allowed me to look at it so critically. I truly believe this film will inspire countless other filmmakers (me included) to produce better works of art. It is very much possible that all of these decisions can be understood within the film and I was just unable to comprehend them. But again, different interpretations of the same film is the reason why cinema has thrived for more than a century. A single film can have whole books written about it and people will still have more to say about it. It is an enchanting medium.

Lastly, a disclaimer. I don’t believe there is anything wrong with the choices the film made and I don’t think I could have done any better. But that’s exactly what these are — just choices. Not good nor bad. All I am attempting to do is understand the reasoning behind these very specific choices. Laal Kabootar is the best movie to come out of Pakistan in a long time, potentially ever, and I loved every second of it. It is available on Starzplay and is the perfect quarantine watch.

Commentaires